Gang Wu, Ph.D.

Abstract

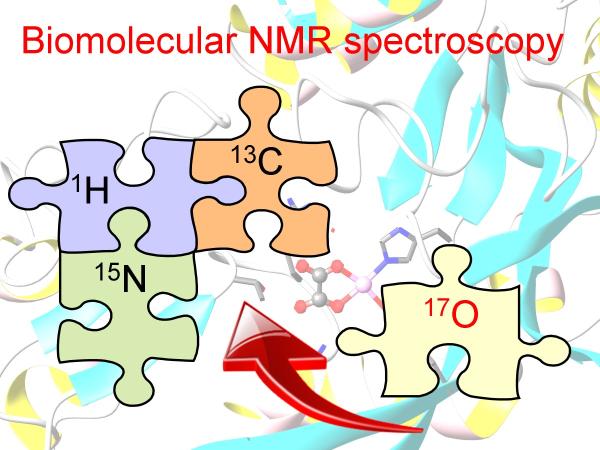

Most chemists would agree that NMR has become an indispensable tool in chemical science. However, all successful NMR applications to date have relied on the detection of atomic nuclei with the smallest non-zero nuclear spin number (I = 1/2) (i.e., 1H, 13C, 15N, and 31P). Any second-year chemistry undergraduate student, after having taken an introduction course on NMR, must have the following question lingering in mind but is too afraid to ask: “Why didn’t we learn any NMR about oxygen--one of the most abundant elements found in organic and biological molecules?” Indeed, the oxygen element remains the only one that is not readily accessible by NMR. So why not? This is primarily because the only NMR-active oxygen isotope, 17O, is exceedingly rare in nature (natural abundance = 0.037%). Furthermore, this oxygen isotope has an unusual nuclear spin number (I = 5/2). Any atomic nucleus with I > 1/2 is called being “quadrupolar” (or “naughty” in layman’s language). The reason quadrupolar nuclei are “naughty” is that they often give rise to very broad NMR signals, from which it is rather difficult to extract any useful chemical information. Now if we view organic and biological molecules as jigsaw puzzles made out of four kinds of pieces (H, C, N, and O), so far chemists have been solving molecular puzzles without the capability of “seeing” one quart of the O pieces! The goal of our current research is to make these missing O pieces “visible”. Would that make the molecular game a little easier?

When: March 7, 2025

Where: North Classroom 1130

Time: 11:00 am - 12:00pm