Introduction

The benefits of bike commuting are plentiful, including lower risk of heart disease and cancer, reducing polluting carbon emissions, and lessening of traffic and wear and tear on roads (Brown, 2019; Center for Climate and Energy Solutions, 2017). Additionally, with ever-increasing fuel and vehicle costs, bike commuting remains a relatively affordable means to navigating the city, a particular benefit for lower income individuals. While bike commuting does present some challenges, namely concerns around commuter safety, protected cycling infrastructure--such as bike lanes that are separated from vehicle traffic—is significantly associated with fewer cycling deaths (Sturtz, 2019). In total, Denver features nearly 270 miles of protected bike lanes throughout the city (DRCOG Regional Data Catalog, 2021). But do bike lanes in Denver serve all communities equally? Specifically, how do they compare in lower-income neighborhoods to higher-income neighborhoods? Further research suggests that while people of all income levels cycle to work, people in lower income households rely more on bicycles for commuting (Cortright, 2019), underscoring the need to evaluate whether bike infrastructure, access, and safety are adequately provided in lower income neighborhoods.

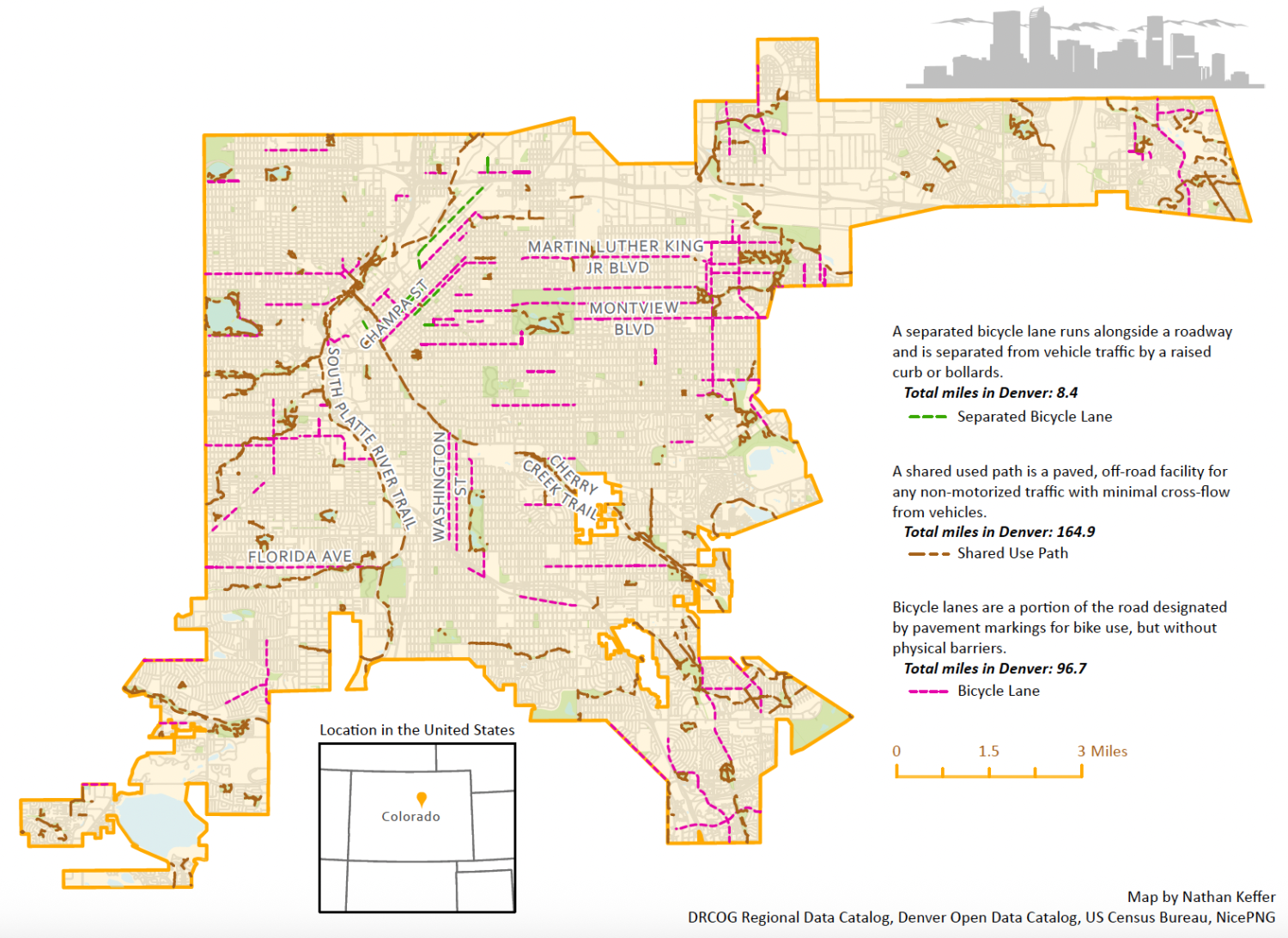

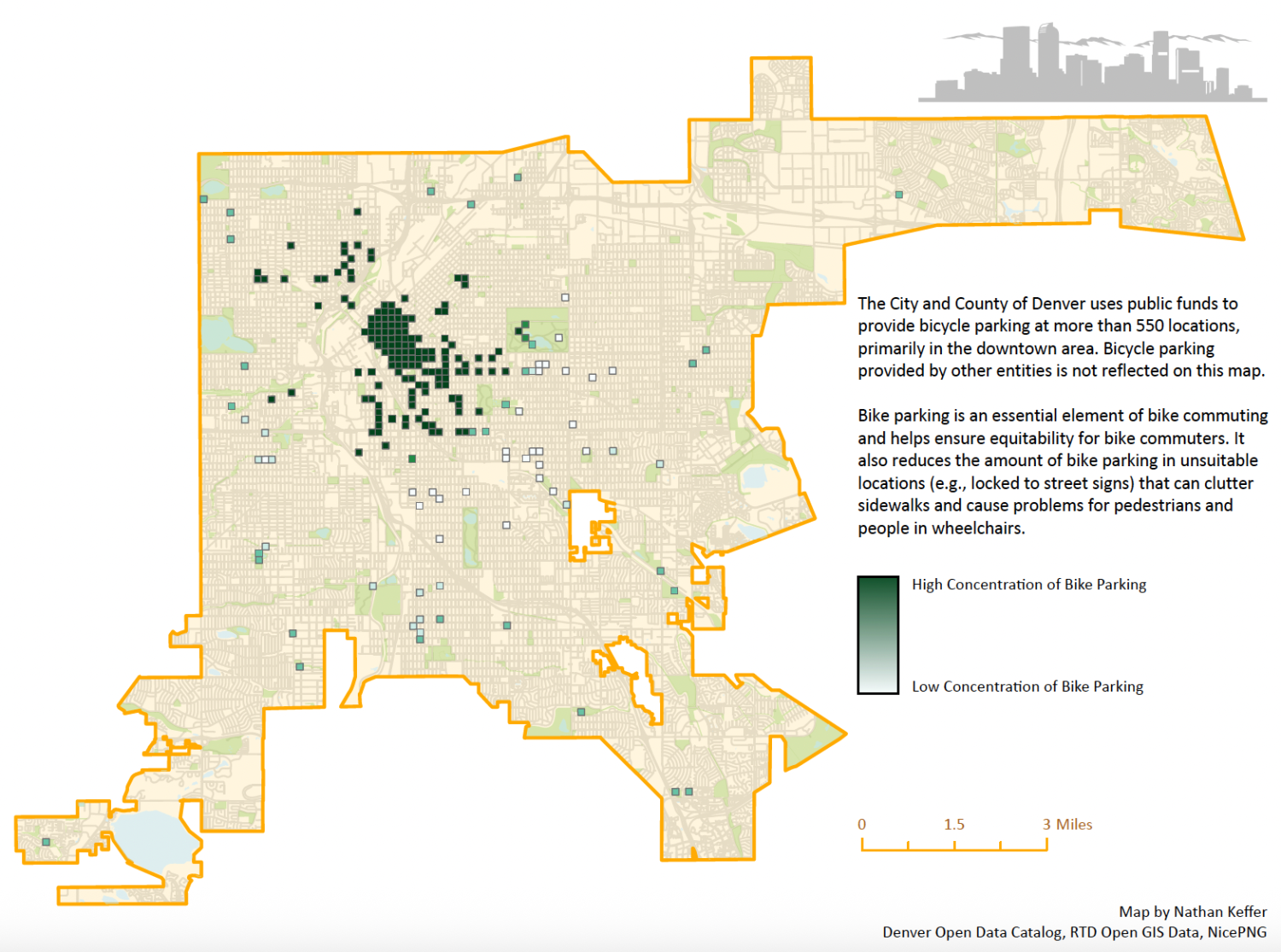

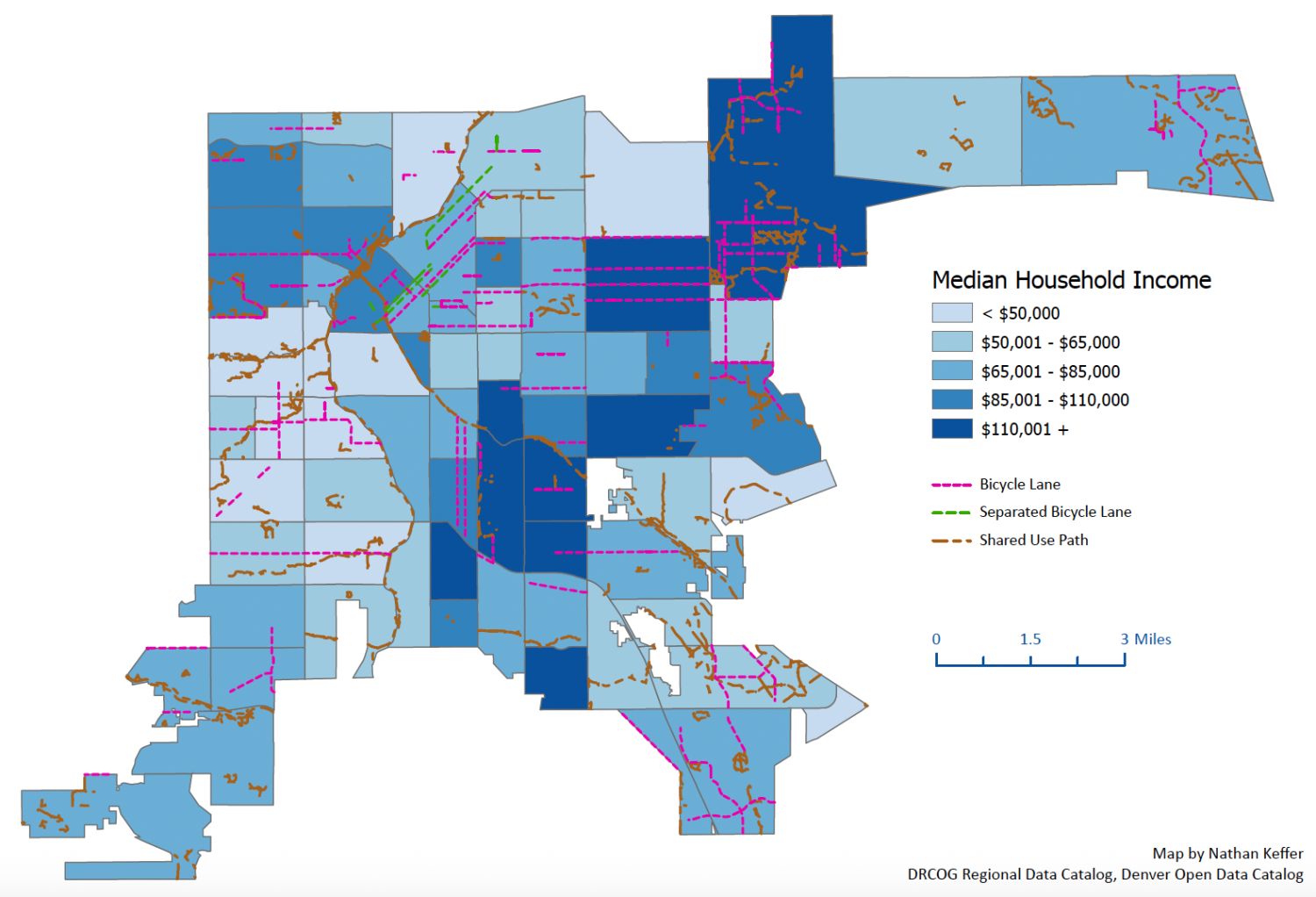

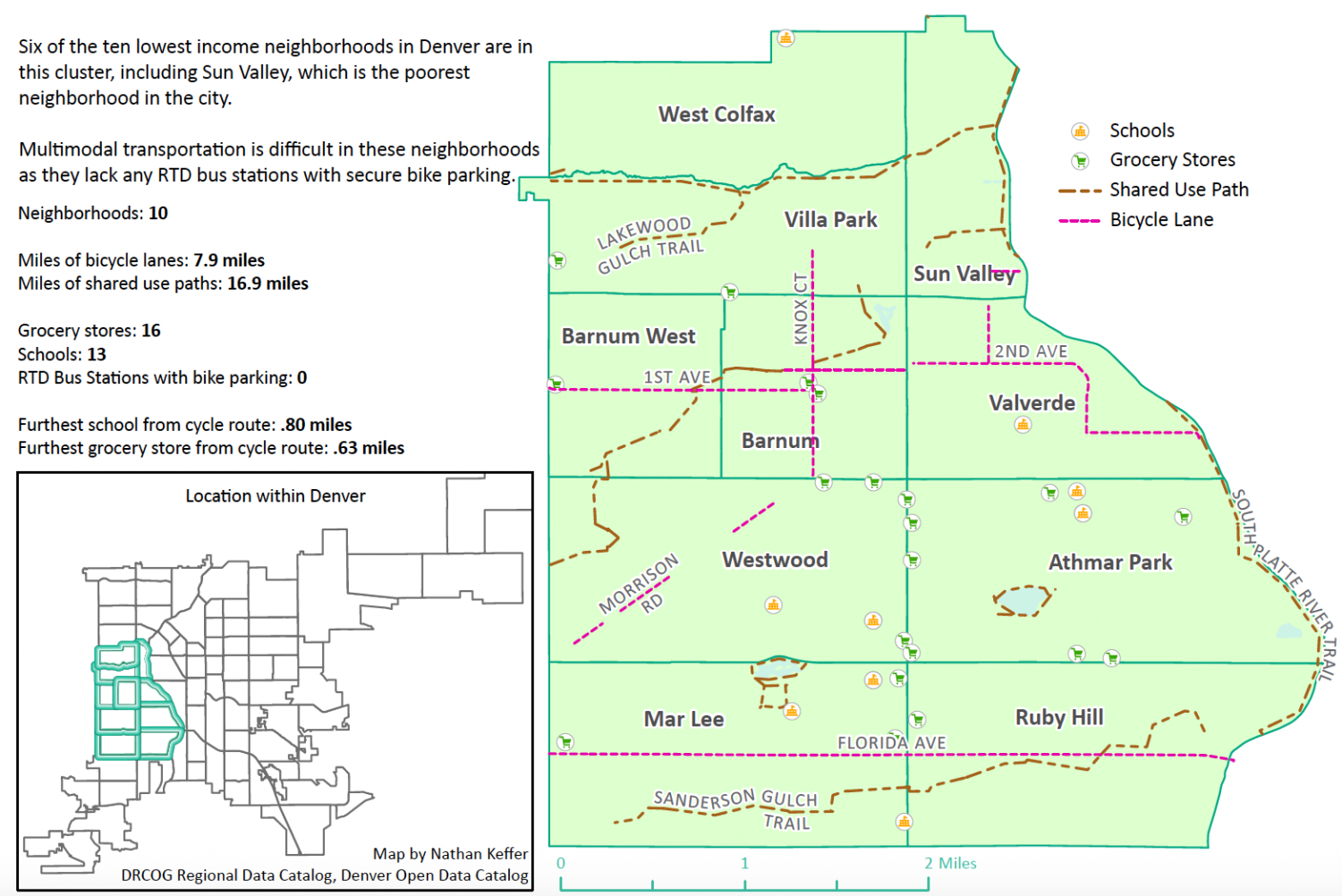

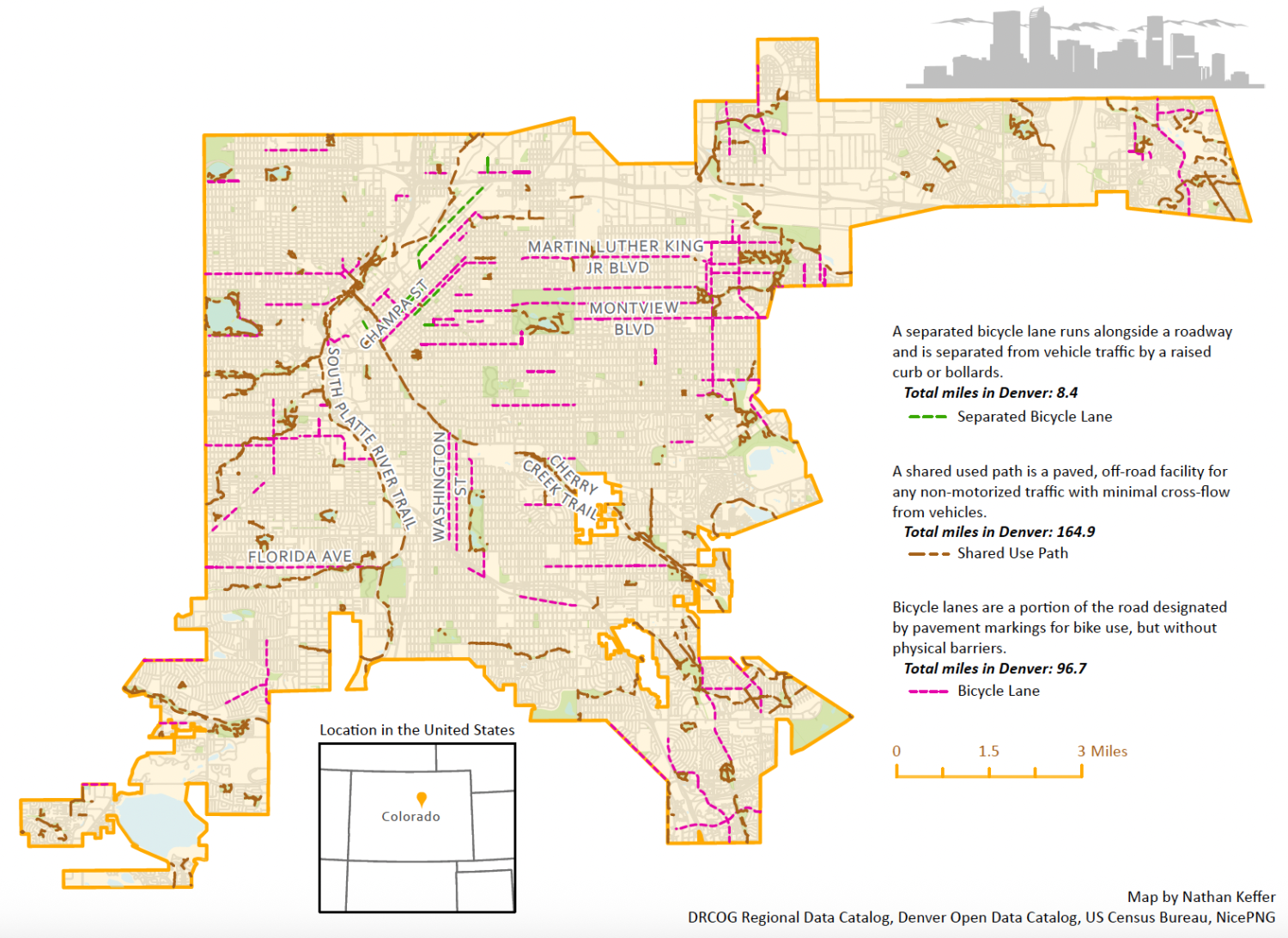

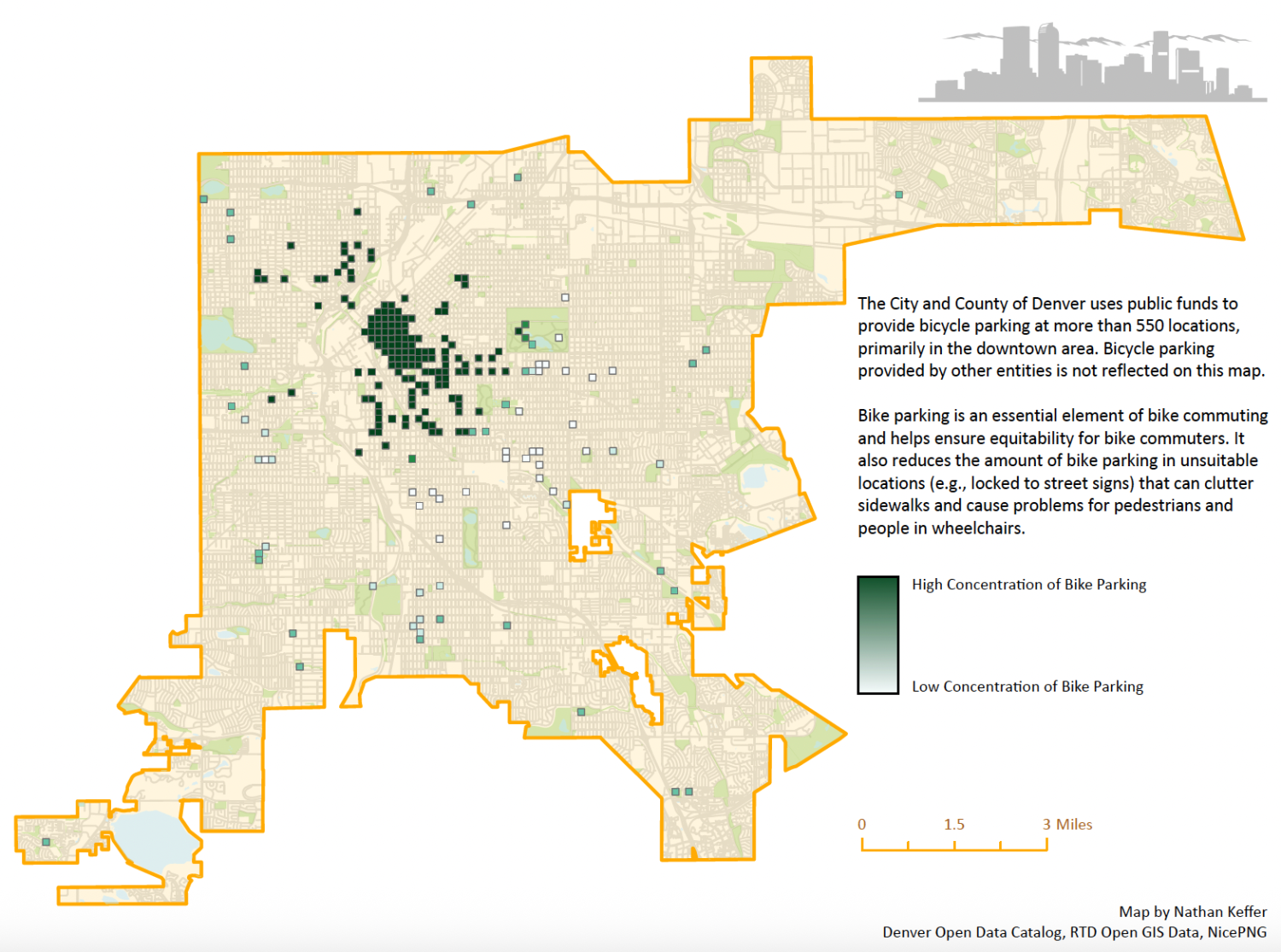

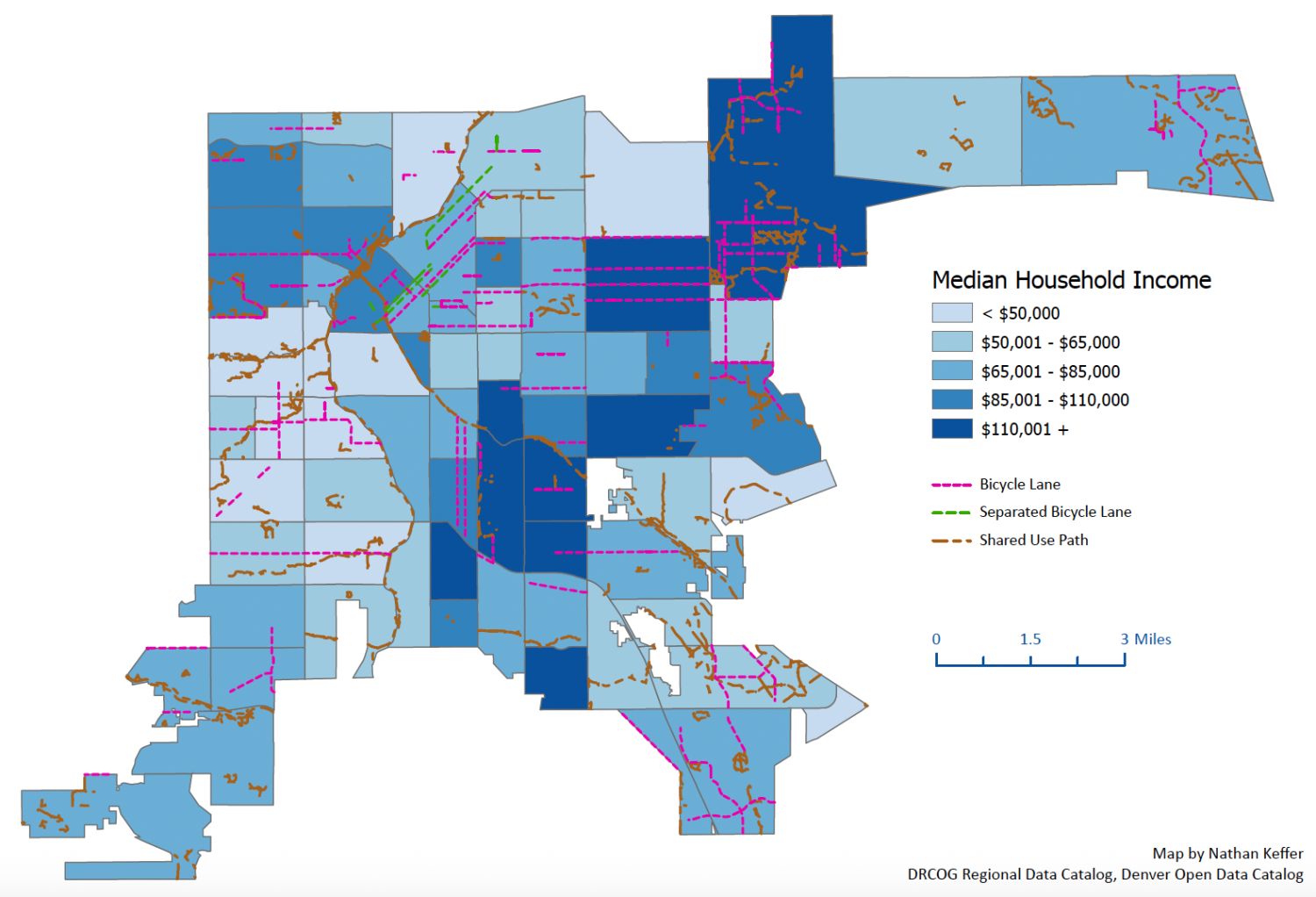

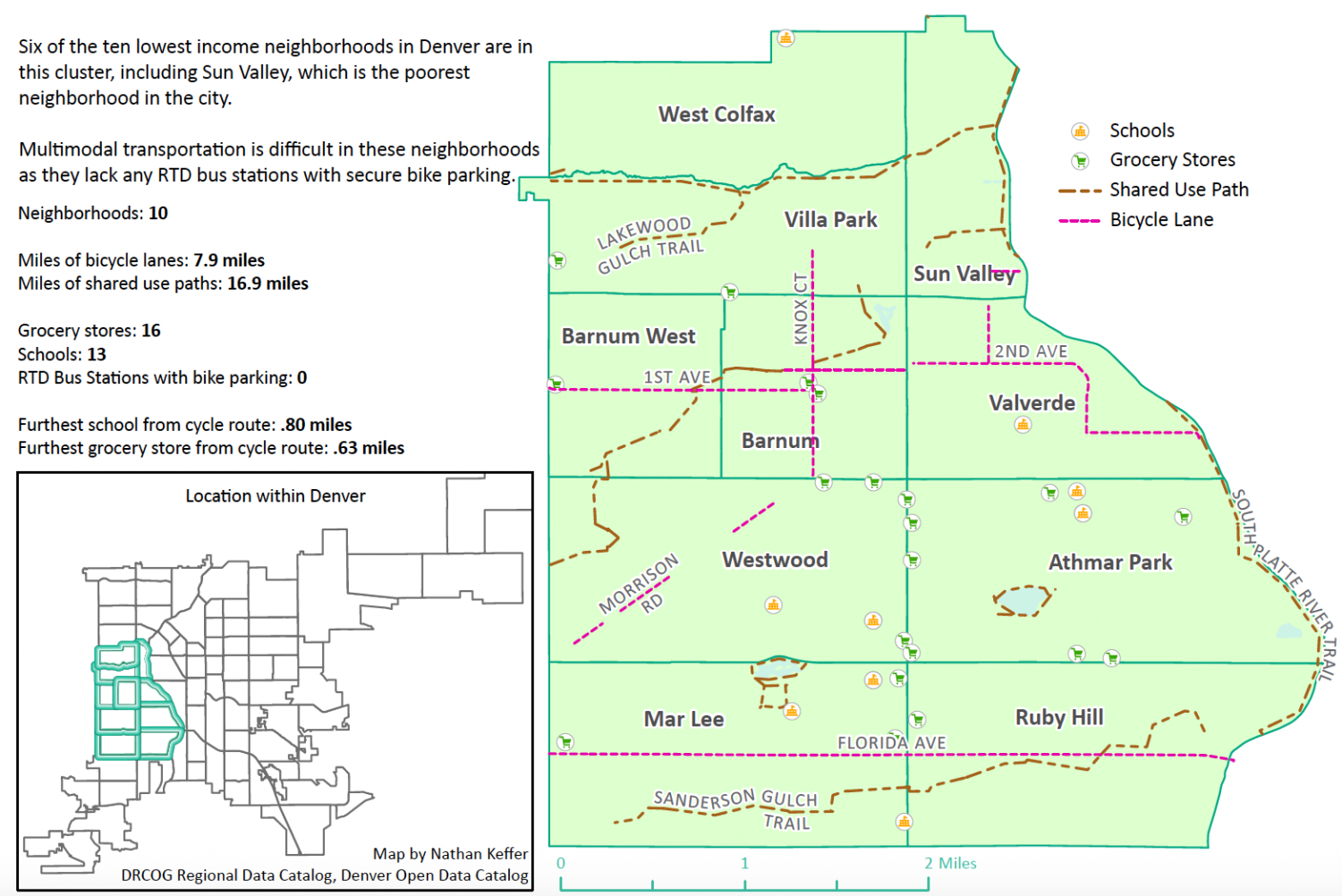

This atlas explores the cycling infrastructure in the City and County of Denver and whether it adequately serves a cluster of lower-income neighborhoods when similarly compared to a cluster of higher-income neighborhoods. Map 1 provides an overview of the nearly 270 miles of separated, protected, and shared use cycling lanes in Denver. Map 2 looks at concentrations of publicly available bike parking. Map 3 breaks down each Denver neighborhood by its median household income (averaged from 2015 – 2019) with data from the US Census Bureau. Map 4 explores a cluster of lower-income neighborhoods in northwest Denver, including the total miles of cycling infrastructure and proximity to important destinations, such as grocery stores and schools. Map 5 provides a similar analysis, but features a cluster of higher-income neighborhoods in central Denver. Maps 4 and 5 also introduce the concept of multimodal transportation, or the linking of diverse forms of transportation such as cycling, walking, or public transit. It does so by mapping Regional Transportation District (RTD) bus stations in Denver that offer secure bike parking. Secure bike parking at bus stations is essential in that it allows bike commuters to safely leave their bicycle at a bus station while utilizing public transportation to complete their trips.

Even with hundreds of miles of bike lanes in Denver, many people turn away from bike commuting due to a variety of factors, including risk perceptions, long distances from important locations, or lack of opportunity to connect bike commuting with other forms of public transportation. Such concerns may be amplified for people of lower socioeconomic statuses, who due to cost of housing, may live further away from schools, grocery stores, and other important destinations. The findings of this project may provide guidance on where to build or improve cycling infrastructure to increase access and opportunity for biking as a means of both transportation and recreation.

Denver Cycle Infrastructure

Bicycle Parking

Median Household Income

Average by Neighborhood, 2015-2019

West Denver

Overview of Lower Income Neighborhoods

Central Denver

Overview of Higher Income Neighborhoods

Analysis & Recommendations

A cursory analysis of two neighborhood clusters in Denver—one consisting of lower income neighborhoods and the other consisting of higher income neighborhoods—reveals little difference in the amount of protected cycling infrastructure. Both neighborhood clusters contained just under eight miles of on-road bike lanes, while the lower income cluster had more than twice the amount of shared used paths, with nearly 17 miles. Each neighborhood cluster contained similar numbers of grocery stores and schools, two locations that are common cycling destinations. One notable difference is the lack of RTD bus stations with bike parking in the lower income cluster. A lack of bus stations with secure bike racks could lead to challenges in using buses for multimodal transportation if there are no secure places to park a bike while using public transportation. Every RTD bus is equipped with a bike rack on the front of the vehicle, but capacity for most city routes is limited to two bicycles.

Finally, the analysis did not reveal significant differences in the distance of the furthest school or grocery store from a protected bike lane. Both neighborhood clusters featured protected bike lanes within one mile from each school and grocery store in the area, meaning an individual would not have to ride with vehicle traffic for more than a mile on their way to any school or grocery store.

| Lower Income Cluster | Higher Income Cluster | |

|---|---|---|

| Miles of Bike Lanes | 7.9 miles | 7.5 miles |

| Miles of Shared Used Paths | 16.9 miles | 7.8 miles |

| Total Miles of Bike Infrastructure | 24.8 miles | 15.3 miles |

| Grocery Stores | 16 | 14 |

| Schools | 13 | 12 |

| RTD Bus Stations with Bike Parking | 0 | 3 |

| Furthest School from Cycle Route | .80 miles | .50 miles |

| Furthest Grocery Store from Cycle Route | .63 miles | .68 miles |

While the neighborhood clusters were a convenient method for at-a-glance comparisons between two distinct areas of the city, it is not sufficient to conclude that Denver’s cycling infrastructure is equitable across the entire city for lower income communities. As is evident in Map 1, “Denver Cycle Infrastructure”, there are significant gaps in cycling infrastructure along much of the “Inverted L”, the corridor of lower income neighborhoods that run parallel to I-70 and I-25. Further analysis is necessary to properly conclude the level of cycling infrastructure equitability across the entire City and County of Denver.

Notably, the lower income cluster of neighborhoods did not feature any RTD bus stations with secure bike parking. Local government and transit districts should take multimodal transportation into account as they continue to develop cycling infrastructure in the region. By adding secure bike parking at bus stops in the featured neighborhood cluster in west Denver, residents of those neighborhoods could more easily link bike commuting to public transit, thus being able to move across the city in less time than cycling, but without having to own or operate an automobile.

Overall, the comparison of two neighborhood clusters in Denver revealed little difference in cycling infrastructure between higher income and lower income neighborhoods. However, this limited analysis is not sufficient to draw a similar conclusion for the whole city. Denver should continue to develop protected cycling infrastructure across the city, with a particular focus on developing multimodal transportation and increasing the ease of cycling for lower income populations, who may rely on cycling as their primary mode of transportation. The more opportunities that individuals have to feel safe while cycling and to connect bike trips to other forms of transportation will help lead to a healthier population and overall reduction in carbon emissions and vehicle traffic along the Front Range.