It’s no secret that sciences’ past was dominated by white men, but many people are working to change its future. Initiatives to expand inclusion focused on curriculum, classroom culture, and pedagogy spanning from pre-k to collegiate levels have been underway for decades –but few scholars have taken time to study the systems that reinforce a feeling of “outsider” status for underserved populations. Paul Le is currently a PhD Candidate in the Integrative Biology Department, and he’s making it his life’s mission to not only better understand science education’s past, but to greatly impact its future. His research focuses on the ways that students form perceptions of science and how faculty (especially at the collegiate level) can change so that students from all background can excel in science classrooms.

It’s no secret that sciences’ past was dominated by white men, but many people are working to change its future. Initiatives to expand inclusion focused on curriculum, classroom culture, and pedagogy spanning from pre-k to collegiate levels have been underway for decades –but few scholars have taken time to study the systems that reinforce a feeling of “outsider” status for underserved populations. Paul Le is currently a PhD Candidate in the Integrative Biology Department, and he’s making it his life’s mission to not only better understand science education’s past, but to greatly impact its future. His research focuses on the ways that students form perceptions of science and how faculty (especially at the collegiate level) can change so that students from all background can excel in science classrooms.

Drawing from the fields of education, anthropology, and sociology, Le employs multiple modalities to interpret how whiteness might impact science education. In a paper he published earlier this year (Towards a truer multicultural science education: how whiteness impacts science education in Cultural Studies of Science Education, with Cheryl E. Matias) Le talks about a theoretical framework that he learned in anthropology: strive to see the usual as unusual, and vice versa. By challenging norms in this way, Le can look at “whiteness” (the hegemonic racial dominance that has become so natural it is almost invisible) and put it under the microscope to see how it operates in science education. Because literature in science education has yet to fully entertain whiteness ideology, Le’s recent paper offers one of the first theoretical postulations of its kind.

One of Le’s early research projects at CU Denver looked at how introductory biology students learn and understand complex systems. He says, “Many incoming students enter an introductory biology class with preconceived notions and misconceptions about systems. Due to the complex nature of biological concepts many students have difficulty synthesizing and organizing information learned in lectures into meaningful forms they can use. They may be unable to see connections across scales and broader impacts.” His early data collection aimed at course reform and is already influencing of active learning interventions on campus.

Le’s own science background was shaped by what he describes as “excellent efforts” on the part of his teachers to make him feel comfortable with STEM studies. Born in the St Louis area, his parents both emigrated from Vietnam, with his father growing up in South Carolina and his mom’s family heading to the Chicago area. They met while Le’s father was on vacation in Chicago and decided to settle “somewhere in-between.” He did his undergraduate work at St. Louis University in Biology, and got into science education research in his sophomore year in Dr. Elena Bray Speth’s lab. The lab he worked in studied how students thought about evolution and natural selection.

Le also has interests in ecology and went to get his Master’s degree at Southern Illinois University Edwardsville in 2014. His future as a multi-disciplinary ground-breaker resulted from getting into the lab of Dr. Richard Essner. He describes Dr. Essner as a “Jack of all Trades,” who provided a lab where students were given the opportunity to pursue their areas of interest in a supportive, collaborative environment. So while Le conducted ornithology and restoration ecology research (in the Upper Mississippi Valley), one of his lab mates was studying morphology in jumping frogs, and another froze turtles to check their respiration rates as they chilled. He had an amazing experience working in the lab, but says he always knew that he wanted to get back to science education. He had the chance when he applied to CU Denver for his PhD studies.

“I chose Denver because I knew I needed to go to a new place to grow as a person,” Le remembers. Professor Laurel Hartley’s lab had been on Le’s radar for a while, as a place where he hoped his aspirations to do more conceptual thinking within the Integrated Biology framework could thrive. Le credits meeting faculty at the university and community advocates in Denver whose dedication and heart inspired him to challenge himself in his educational pursuits, “I saw what they’re doing, the passion and energy in what they’re doing, and it’s hard to see all that and not what to be a part of it.”

Le connected to advocates in the LQBTQ community his first semester at CU Denver by helping out on the host committee and presenting at the national Creating Change 2015 Conference. He made connections though that events that he cherishes to this day: people in education, local government and the non-profit world who helped make Denver feel like a community he was deeply connected to and invested in. He fell in love with the city of Denver and its diverse people, and this fed his desire to integrate a fight for further equity and access into his academic career.

“I want to make sure that I’m part of the movement that’s giving students a sense of belonging, and that they have access to resources that they need to thrive and to be successful. I want to reform classrooms so that we aren’t just reproducing the same norms and values,” says Le. He’ll spend his career working, “to really create a classroom experience that reflects what students know and what they need.”

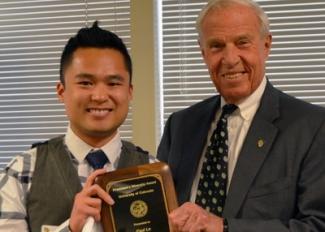

Last year, Le received the President's Diversity Award for his research in multicultural science education and his service on behalf of LGBTQ issues. In his work as part of the University’s Active Learning grant, Le surveyed and collected multiple data points on CU Denver undergraduates in STEM classes and produced data for faculty, giving baseline intelligence about students currently in their classrooms. Additionally Le included anecdotes about the student experiences in those students own words, reinforcing the impact of the numbers with the human connection he hopes all faculty will strive for as educators. Le sights studies where students say they felt their professors were making an effort to know them as people, and that those studies show how much that attitude can influence student success.

Focused on reforming higher education, he will defend his dissertation in the months to come and move onto an academic position where he can influence college culture and pedagogy. Taking an anthropological and sociological approach, he hopes to encourage those in charge of science classrooms to question common practices in order to create classrooms better designed for underrepresented populations to succeed. Taking into account students individual histories and identity production, Le hopes faculty will make efforts so that all students can feel like they belong in the science world.

“Faculty don’t need to be completely transformed, but if I can even get some faculty see their students in a slightly different light – asking them ‘how’s your day going?’ and making them feel welcome – that can make all the difference.”