Over a decade of work, anthropologist gains knowledge into dimensions of human experience

While many faculty members spend their summers researching, not many willingly choose to spend them in the harsh conditions that California's migrant farmworkers experience. Sarah Horton, Associate Professor of Anthropology, has been studying and publishing research on the complex relationship between immigration policies and healthcare for more than a decade. She spent much of this time in the field with a group of farmworkers getting a first-hand account of their experiences.

While many faculty members spend their summers researching, not many willingly choose to spend them in the harsh conditions that California's migrant farmworkers experience. Sarah Horton, Associate Professor of Anthropology, has been studying and publishing research on the complex relationship between immigration policies and healthcare for more than a decade. She spent much of this time in the field with a group of farmworkers getting a first-hand account of their experiences.

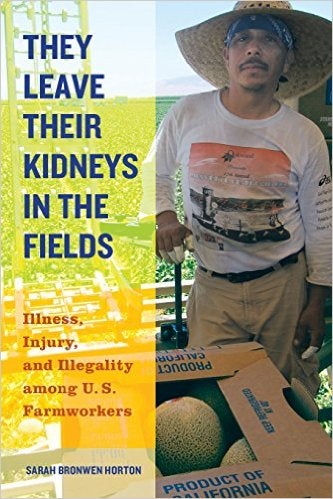

This July, Horton published They Leave Their Kidneys in the Fields: Illness, Injury, and Illegality among U.S. Farmworkers (University of California Press). The book was published as part of the Press' Public Anthropology series—a series intended to reach a popular audience--and focuses on the high rate of heatstroke deaths among farmworkers in California's Central Valley. CU Denver had the opportunity to sit down with her to talk about the book and the research that led her to write it.

CU Denver: First of all, can you explain the intriguing title of the book?

Horton: This was the statement of one of my interviewees when we were discussing deaths from heatstroke. She said, quite poetically, "They come here, they work, and they leave their kidneys in the fields, they leave their lungs in the fields." It's a truism in the Central Valley that heatstroke dries up the kidneys. And recent research in Central America, where chronic kidney diseases of unknown origin are an epidemic, does suggest that chronic exposure to heat and dehydration play a role in kidney failure.

CU Denver: During your research you followed 15 individuals for more than 10 years, gaining intimate access to their economic struggles and health challenges. What kind of insights do you think you gained from this kind of person-to-person study that you couldn't have gotten from a larger, more statistical study?

Horton: Most of the statistical studies focus on farmworkers' lack of knowledge about how to prevent heat illness or their unhealthy practices regarding prevention. My thought is that we need to understand the multiple forces that would make someone basically work themselves to death, which is what often happens in California's fields. We need to understand the ways that migrant farmworkers are exceptionally vulnerable due to immigration, labor, healthcare, and food safety policies. There are so many issues about immigrants' lives and farmworkers' lives that are poorly understood simply because of that lack of in-depth knowledge. That kind of intimacy allowed me to understand things like "working as a ghost," which doesn't really appear in other studies, news articles, or literature.

CU Denver: Your research found that some agribusiness employers and labor supervisors participate in coercively masking the identity of their workers to subvert immigration and labor laws. Can you tell us a little more about "ghostworking" or trabajando fantasma and how it relates to illness and injury? How is "ghostworking" different from working without papers or with false papers?

Horton: Migrants "working as a ghost" have been given valid papers belonging to other individuals to work—usually their labor supervisors. So they have a great concern about being implicated in identity theft. As a result, ghost workers are much less likely than those working false papers or those working under the table to report their illnesses or injuries to their supervisors. The Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act, which passed in 1996, made workers—both legal migrants as well as undocumented migrants—much more vulnerable if they were convicted of a charge like identity theft. It makes even legal residents deportable if they are convicted. In the past, non-citizen legal residents were only deportable if they were convicted of violent offenses. So the Act dramatically increased the penalties involved in charges of things like "identity theft," as it made it something a legal resident could be deported for.

Horton: Migrants "working as a ghost" have been given valid papers belonging to other individuals to work—usually their labor supervisors. So they have a great concern about being implicated in identity theft. As a result, ghost workers are much less likely than those working false papers or those working under the table to report their illnesses or injuries to their supervisors. The Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act, which passed in 1996, made workers—both legal migrants as well as undocumented migrants—much more vulnerable if they were convicted of a charge like identity theft. It makes even legal residents deportable if they are convicted. In the past, non-citizen legal residents were only deportable if they were convicted of violent offenses. So the Act dramatically increased the penalties involved in charges of things like "identity theft," as it made it something a legal resident could be deported for.

What's interesting is that it isn't just undocumented immigrants who are coerced into "working as a ghost." I found that labor supervisors use this strategy not only to disguise their violation of immigration laws, but also their violations of wage and hour laws. In California, farmworkers are legally entitled to overtime pay when they work in excess of 60 hours a week or 10 hours a day. In order to avoid paying this overtime, labor supervisors would sometimes make workers of all legal statuses work under the identities of other people on Sundays. And this strategy can also benefit labor supervisors economically because they get often get a kickback from the people who own the papers that are provided to employees to be worked.

CU Denver: Given the sensitivity of the topics you were researching, how did the workers and labor supervisors react to your presence in the fields?

Horton: When I first went into the fields, in 2005, I called several times to try to talk to farms about coming to observe, but they never returned my calls. So I wound up just sort of going into the fields to find out if I would be able to observe that day, knowing that I might not. With the labor supervisors it would vary, sometimes the contractor would roll up within minutes and ask me to leave, and in other cases I was able to stick around awhile.

I built rapport with the workers by trying whenever possible to help people with the small things that I could do, whether it was interpreting for people, filling out paperwork, finding phone numbers, or printing out information about doctors or surgeons for them. After a while, people would actually be upset if I didn't come visit them when I went to the valley. Over time, they were very welcoming of my presence.

CU Denver: In what ways does your research suggest labor laws and immigration policies could change in order to protect the lives of migrant workers that many industries, like agriculture, depend on?

Horton: There is a new bill to provide standard overtime pay to farmworkers that just passed the California State Senate and is now going to Assembly. If passed, this would make California the first state to provide farmworkers overtime at the national standard rate of 8 hours a day, 40 hours a week. These kinds of labor laws are important for people to advocate for in every state. They can have an effect not only in terms of economic security, but also in terms of exposure to heat and heat illness. Farmworkers have been historically excluded from labor protections that we grant workers in other industries for a variety of reasons. Legislative changes are important, but there also needs to be adequate enforcement and that is the piece that has been missing in California and many other states.

The POWER Act is another proposal by the National Immigration Law Center that would grant workers who alerted authorities to an abuse by their employer temporary stay of deportation or work authorization. It's a way to help workers avoid employer retaliation if they were to disclose information about practices like identity masking. The POWER Act would help mitigate the extreme workplace vulnerability that the punitive laws that were passed in the 1990s helped create. These are just some of the changes in law that I discuss in my Conclusion to help improve farmworkers' health and labor circumstances.

CU Denver: How does your field research inform the classes that you teach here at CU Denver?

Horton: I teach a class on migrant health and globalization and migration. Both of these involve students in research projects that assist migrants in some way. I like to try to introduce students to the challenges and the rewards of working with migrant populations.

CU Denver: Now that this book is complete, will you continue to follow these families, or will your research take a new direction?

Horton: There are a couple of spinoff projects that I'm involved in now. One of them is basically trying to document exactly how our occupational safety and public health surveillance systems keep track of heat deaths and heat illnesses to try to find the gaps in reporting.

The other project is about food safety policies and how they affect workers. A lot of growers are being required by large retailers to comply with certain food safety rules in order to assure the public of the safety of their produce. To be compliant with the audits from private industry, as well as the state, workers are restricted from bringing their own water supplies into the fields because it is seen as a potential source of contamination. On the one hand, the state is overseeing these food safety regulations and, on the other hand, they are trying to enforce the new heat illness regulations, which emphasize rehydration. There is not a lot of recognition about how these two policies are in conflict with each other. I just sent a report to the state about the ways these rules affect workers when they harvest melons, making recommendations about where to place water jugs so that workers can actually have access to water if they can't bring their own into the fields.

CU Denver: On a more personal note, what have been the most rewarding and challenging parts of conducting research with the migrant workers and families you have interviewed?

Horton: It's broadened my knowledge of dimensions of human experience that I wasn't aware of before. It's been rewarding to be able to work with this group of people for ten years. I'm really grateful to them for allowing me to stay in contact with them. I think in terms of challenges, it can be very emotionally hard to see the kinds of difficulties they face both in terms of work and in terms of personal health challenges.

Rianna Riegelman is a CU Denver and CLAS alumna (1999) with a BA in English Writing. She works as a writer, editor, and graphic designer in Denver and Boulder.