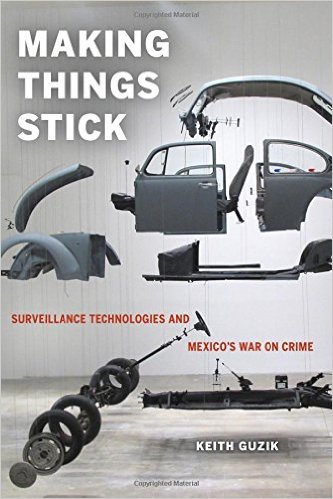

The title of Associate Professor of Sociology Keith Guzik's new book—Making Things Stick: Surveillance Technologies and Mexico's War on Crime (University of California Press)—has earned him more than one curious look. But he can explain. "There's this growing theoretical current in sociology right now that looks at the way our everyday lives are mediated through technology. These material things (phones, cars, computers) we really can't conduct our lives as social beings now without them. But there's fear about Big Brother and how technologies bring surveillance into our lives." Making Things Stick addresses this intersection.

The title of Associate Professor of Sociology Keith Guzik's new book—Making Things Stick: Surveillance Technologies and Mexico's War on Crime (University of California Press)—has earned him more than one curious look. But he can explain. "There's this growing theoretical current in sociology right now that looks at the way our everyday lives are mediated through technology. These material things (phones, cars, computers) we really can't conduct our lives as social beings now without them. But there's fear about Big Brother and how technologies bring surveillance into our lives." Making Things Stick addresses this intersection.

"In sociology we have the chance to do empirical research or more theoretically inspired work, and this was my chance to play around with both," Guzik says. His research focused on Mexico, but its lessons apply more widely to trends in security policy. Guzik says, "Governments are concerned less and less about people as individuals, they don't necessarily care about you as a person because they think if they can track your car or your phone that's just as good."

Guzik published the book Arresting Abuse: Mandatory Legal Interventions, Power, and Intimate Abusers (Northern Illinois University Press), in 2009. Looking for a new topic to explore, Guzik decided to use his background in legal and technology studies to dive into concerns about "Big Brother" surveillance that have defined our post 9/11 world. The challenge was figuring out a unique take on the subject.

Much of the research on state surveillance at the time, Guzik says, was focused on the US and Europe, relatively secure places where issues of personal liberty resulted in critiques of governmental overreach. Mexico, embroiled in a war on drugs that was fueling violence and public fears of crime, provided an interesting case study for how surveillance technologies and information systems operate and how they are perceived in contexts of extreme insecurity. He applied for and received funding to study these issues from the National Science Foundation's Law and Social Science and Science, Technology, and Society programs.

Over the course of 3 separate trips to Mexico from 2010 to 2012, Guzik conducted field research to study the implementation of 3 governmental programs: an electronic car registration program that would place an RFID tag (a device a bit smaller than a smartphone) onto the windshield of every vehicle in Mexico; a mobile phone registry requiring everyone to register their cell phone number with the government; and a national ID card based on biometric data such as iris scans.

As a sociologist Guzik was primarily interested in studying the relationships among these surveillance technologies, crime control, and perceptions of governmental authorities. What he quickly learned was that implementation of surveillance programs in Mexico was difficult for several reasons. He remembers, "These programs were all failing, struggling to get off the ground, and that really changed the focus of my research to how governments manage or try to launch programs like this. And that's interesting because often when people think of Big Brother programs they think about the NSA and government being able to do what it says it's going to do."

Guzik realized that the Mexican government's struggle to launch these initiatives was the real topic to address. To do this, he gained access to institutions and employees in Mexico, including administrators and frontline workers with the Public Registry of Vehicles in Zacatecas and Sonora and their federal counterparts in the Mexico City offices of the Executive Secretary of the National System for Public Security. He describes their cooperation as remarkable, and says his work would not have been completed without it.

Guzik realized that the Mexican government's struggle to launch these initiatives was the real topic to address. To do this, he gained access to institutions and employees in Mexico, including administrators and frontline workers with the Public Registry of Vehicles in Zacatecas and Sonora and their federal counterparts in the Mexico City offices of the Executive Secretary of the National System for Public Security. He describes their cooperation as remarkable, and says his work would not have been completed without it.

As a result, Making Things Stick comes from a place of great access. The introductory chapter in particular is an excellent primer for anyone interested in issues of surveillance technology. The entire book is available free of charge through the University of California Press's innovative on-line Luminos publishing initiative, which makes books like Guzik's more widely available throughout the globe.

"The failed experiment of the Mexican security programs demonstrates that state surveillance technologies yield neither the secure utopia nor the police state dystopia promised by their supporters and opponents," Guzik said. "The inherent uncertainty of technology-based state surveillance programs ensures that civic involvement in the work of crime control will remain critical to the shape of security governance in the future."

Recently, Guzik has been expanding his focus on materiality and crime control. In June the New Republic republished an op-ed Guzik wrote with esteemed sociologist Gary T. Marx titled, Regulating Cars Made Them Safer. Can We Do the Same with Guns? The article further develops arguments around the balance between owning material objects (in this case cars and guns), exercising our rights as citizens, and meeting our security obligations as a society. "Think about the DMV, and having to get your paperwork in order so that you can legally operate your car," he explains. "Vehicle registration is part of the way you discipline yourself as a car owner. We don't do that with guns and the second amendment. But we could and should."

Guzik says his future research will continue to look at the relationship between technology and law enforcement. Next in line is beginning research on police body cameras and continuing to think about security and surveillance technologies 15 years after 9/11. "We haven't done a good job so far of thinking about how engrained into our everyday world things like cars and cameras are. We can do better."