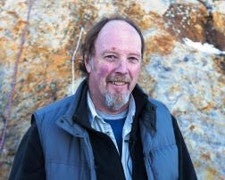

Emeritus Geology Associate Professor Martin Lockley

A serious scientific question, according to Emeritus Geology Associate Professor Martin Lockley and his international team of collaborators: Were dinosaurs hot, as in hot lovers?

Answer: Probably yes, when they were "in heat."

It's common knowledge that some dinosaurs had flamboyant head gear: horns, frills and crests. Add to that the relatively new evidence that many had feathers and were related to birds, and a whole new vista of possibilities opens regarding their courtship, mating and display activities. Dinosaurs engaged in mating behavior similar to modern birds, leaving the fossil evidence behind in 100-million-year-old rocks. Over the past several years Lockley, a paleontologist, has led a research team that discovered large 'scrapes' in the prehistoric Dakota sandstone of western Colorado. These ancient scrapes are similar to those resulting from a behavior known as 'nest scrape display' or 'scrape ceremonies' among modern birds, where males show off their ability to provide by excavating pseudo nests for potential mates.

"These are the first sites with evidence of dinosaur mating display rituals ever discovered, and the first physical evidence of courtship behavior," Lockley says." These huge scrape displays fill in a missing gap in our understanding of dinosaur behavior."

Martin Lockley (right) and Ken Cart pose beside large dinosaur scrapes in western Colorado

After a press conference at Dinosaur Ridge last month, news of these discoveries has been picked up by more than 800 media outlets around the world, in more than 10 countries, including the Los Angeles Times, Guardian, Smithsonian, Christian Science Monitor, and USA Today. According to the university's media monitoring service, over two billion people have seen the story, which the hometown Denver Post began with the catchy sentence: "A skilled Colorado dinosaur tracker has unearthed 100 million-year-old dino love nests in Denver's backyard."

"The best candidate for the amorous scrape-making dinosaurs is the probably the carnivore known as Acrocanthosaurus" said Lockley. Like birds, some of their closest cousins, the carnivorous theropod dinosaurs, may have engaged in colorful display. While popular culture may conceptualize carnivores like Allosaurus and T. rex as cold-blooded killers, they may have been amorous as well. Some of the evidence is indirect, based on theropod family tree relationships to birds—some species of which are masters of showy displays, peaking in the breeding season. But Lockley's team's discovery lends much more direct evidence. The study was published in the journal Scientific Reports (Nature Publishing Group) on January 7, 2016.

Lockley, a world-renowned expert on dinosaur footprints, found evidence of more than 50 dinosaur scrapes, some as large as bathtubs, in an area where tracks of carnivorous and herbivorous dinosaurs have also been confirmed. The display arenas, called 'leks' were found in two National Conservation Areas (Dominguez-Escalante and Gunnison Gorge) on property permitted by the Bureau of Land Management near Delta, Colorado. Lockley also discovered evidence of mating areas at Dinosaur Ridge, a National Natural Landmark in Morrison, just west of Denver.

This new fossil evidence supports theories about the nature of dinosaur mating displays and the evolutionary driver known as `sexual selection.' Since prehistoric times, males looking for mates have driven off weaker rivals. Females, meanwhile, have chosen the most impressive male performers as consorts. Similar sexual selection behaviors are common in mammals and birds. But until now scientists could only speculate about dinosaur mating behavior.

"The scrape evidence has significant implications," says Lockley. "This is physical evidence of pre-historic foreplay that is very similar to birds today. Modern birds using scrape ceremony courtship usually do so near their final nesting sites. So the fossil scrape evidence offers a tantalizing clue that dinosaurs in 'heat' may have gathered here millions of years ago to breed and then nest nearby."

Lockley's 15-strong tracker team, while including six Colorado residents, is truly international. Three Koreans represent the National Research Institute of Cultural Heritage, which partly funded a three-year joint dinosaur tracking project in Colorado and eastern Utah. The team also includes two Canadians, a Chinese colleague, and two Polish paleontologists, who, like Lockley, are involved with a new museum devoted to tracks in eastern Utah called Moab Giants. Three Bureau of Land Management (BLM) employees round out the team having worked closely with the trackers for several years assisting in state-of-the-art 3D photogrammetric documentation of the sites at three locations on BLM-administered land in western Colorado.

"We have to imagine several of these large dinosaurs, with feet up to 18 inches long, and bodies 20–25 feet, scraping sandy substrates near the shores of the famous Cretaceous gulf known as the Western Interior Seaway. They were probably not only excited, but quite vocal," says Neffra Matthews, a BLM paleontologist at the National Operations Center in Denver. "It would have been impressive."

Lockley and his team were unable to remove the scrape marks from the gigantic slabs of rock without damaging them. Instead, they created 3D images of the scrapes using a technique of layering photographs called photogrammetry. They also made rubber molds and fiberglass copies of the scrapes that are being stored at the Denver Museum of Nature and Science. "These huge trace fossils tell a fascinating story," says curator Joseph Sertich, adding, "they fill a gap in our understanding of dinosaur behavior."

Lockley cautions that some paleontologists have asked if there might be other explanations for the scraping. "We explored other possibilities." He explains that digging for water or food by carnivores was very unlikely, as water was abundant in these environments. Likewise, these would not be actual nest sites because there are no eggshells or bones of hatchlings, and in any case sitting in a nest for long periods would smudge out the very clear scratch marks. Aggressive male theropods might have used suitable sites to make territorial displays, but these, say the team, would be difficult to distinguish from display arenas. "The display arena hypothesis is clearly the most convincing" insist Richard McCrea and Lisa Buckley, team members and directors of the Peace Region Paleontological Research Center in British Columbia.

The scrape evidence has several significant implications. Modern birds using scrape ceremony courtship, usually do so near their final nesting sites. This means that finding the right type of scrapes could mean a nearby nest colony. No one has ever found one in the Dakota Sandstone, where acid conditions have removed most calcium carbonate shells, and perhaps eggshells as well. But the scrape evidence is a clue that "hot dinosaurs," congregated here in the spring breeding season and may have then nested nearby.

Adapted from an article by Emily Williams, University Communications, January 7, 2016.